Harvard scientists discuss promise and peril of emerging IVG technique

In vitro fertilization has transformed reproductive medicine and sparked a number of therapeutic and diagnostic breakthroughs.

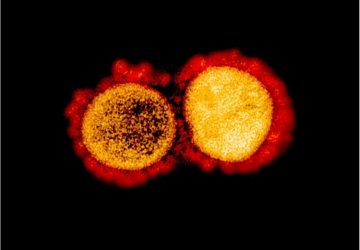

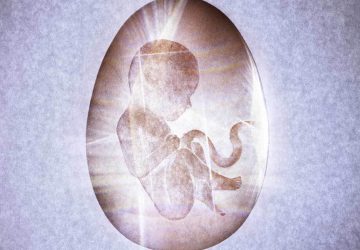

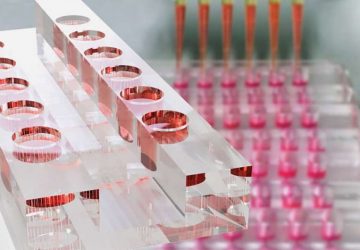

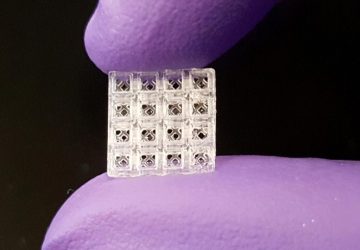

Now a new, still experimental, technique known as in vitro gametogenesis (IVG) is poised to usher in the next era in reproductive and regenerative medicine. The approach—thus far successful only in mice—allows scientists to create embryos in a lab by reprogramming any type of adult cell to become a sperm or egg cell.

In a newly published commentary, a trio of scholars argue that while IVG carries a promise to unravel the fundamental mechanisms of devastating genetic forms of infertility and to pave the way to a range of new therapies, the technique also raises a number of vexing legal and ethical questions that society should address before IVG becomes ready for prime-time clinical use in human patients.

The article, published Jan. 11 in Science Translational Medicine, is authored by I. Glenn Cohen, professor at Harvard Law School, George Q. Daley, Dean of Harvard Medical School, and Eli Y. Adashi, professor of medical science and former Dean of Medicine and Biological Sciences at Brown University.

IVG holds enormous potential not only as a treatment for infertility, but also for a constellation of currently untreatable diseases, the authors write. Additionally, they note, the technique may provide an inexhaustible supply of lab-made embryonic stem cells for research and therapeutic use as a tantalizing alternative to scarce human embryonic stem cells, which are currently in limited supply due to ethical considerations and regulatory restrictions.

Yet, the authors say, such promises come with some worrisome scientific, legal and ethical challenges, such as the need for rigorous scientific protocols to ensure that any reproductive cells created through IVG are free of genetic aberrations, the threat of improper commercialization of IVG for large-scale embryonic generation and the use of preimplantation genetic screening to create “designer” offspring.

The authors acknowledge that clinical uses of IVG in the foreseeable future remain improbable at best. The impact of IVG, they say, will likely be limited to enhancing the science of germ cell biology. Yet, they caution, some clinical uses may arrive much sooner than anticipated, given the breakneck speed at which science and medicine are advancing.

To prepare for that time, scientists, bioethicists, policymakers, legal scholars and the public should initiate and maintain a vigorous conversation about the implications of IVG.

“Emerging technologies carry enormous promise but can also be profoundly disruptive. Aligning their promise with ethical and legal considerations is an imperative not only for scientists but for the society as a whole,” said George Q. Daley, Dean of Harvard Medical School. “To do so, we must initiate vital conversations early and engage the public. Nothing less will do on our quest to ensure that we strike the right balance between our most audacious scientific pursuits and our core ethical and legal principles.”

The authors go on to say that the United States might be wise to borrow a page from the U.K.’s playbook, where a protocol focused on safety, ethics and public consultation has recently led to the launch of government-sponsored clinical studies of mitochondrial replacement therapy, a lab-based procedure that replaces defective mitochondrial DNA in a woman’s egg cells with healthy DNA to avert passing the defects to her offspring.

source :