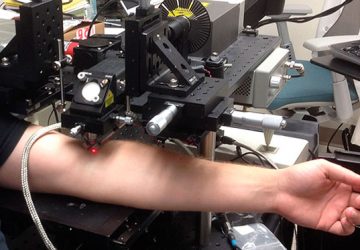

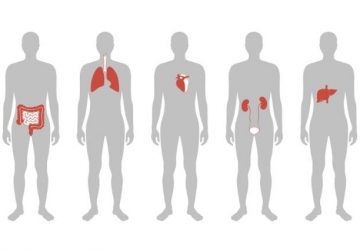

Cyberdyne, the Japanese robotics company with the slightly suspicious name, has just gotten approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to begin offering its HAL (Hybrid Assistive Limb) lower-body exoskeleton to users in the United States through licensed medical facilities. HAL is essentially a walking robot that you strap to your own legs; sensors attached to your leg muscles detect bioelectric signals sent from your brain to your muscles telling them to move, and then the exoskeleton powers up and assists, enhancing your strength and stability.

The version of HAL that the FDA has approved is called HAL for Medical Use, and it’s designed to help people with lower limb disabilities get better at walking on their own. There are other exoskeletons that help rehabilitate people through physical walking motions, but HAL is unique in the way that it relies on a mixture of voluntary control and autonomous control, using the wearer’s own nervous system to signal the robot when and how to move. According to Cyberdyne, this makes the rehabilitation process more effective, because it’s not just the robot moving— it’s you.

HAL for Medical Use has been available in Japan for several years now; here’s a video from Japan Times showing how it works in practice:

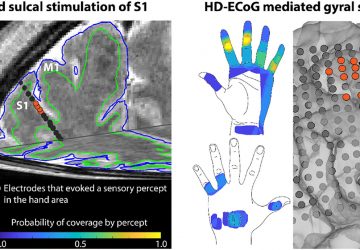

HAL establishes interactive biofeedback according to intention-based motion information from the brain-nervous system and activating sensory systems like muscle spindle fibers to form a neural loop between the brain-nerve system and the musculoskeletal system. Even if the patient is unable to generate enough muscle strength to move due to motor dysfunction, the treatment is able to repeatedly realize actual movement that is in sync with the motion intent of the brain while avoiding excessive burden on the brain-nerve-muscle systems, thus making functional improvement/regeneration possible. The HAL will not move until it detects an electrical signal, ideally one of the users attempting to move the limb being assisted. This creates a stronger cause-and-effect dynamic between the user and powered exoskeleton.

Since many lower limb disabilities are caused by disconnects between what the brain wants to do, instructions that the nervous system transmits, and the resulting muscle movements, HAL is intended to actively help users re-form those connections. Even if your muscles aren’t responding properly when your brain signals them to “walk,” having HAL intercept those signals and move your muscles for you can accelerate the learning process by which your brain and muscles figure out how to work together again. Cyberdyne calls this process “an interactive biofeedback loop,” and says that “this repeated movement strengthens and adjusts the connections between the neurons in the brain and spinal cord and the connections between the neurons and muscles, promoting improvement and regeneration of physical functions.”

At CES 2011, I tried out an older, non-medical version of this device, called HAL for Living Support. The interface is the same as the new one, though, so I have some experience with how this thing works and what using it feels like. Here’s an excerpt from the 2011 article I wrote for the now defunct DVICE.com about testing out HAL:

Cyberdyne’s HAL (Hybrid Assistive Limb) exoskeleton is designed to augment the strength of the wearer by a factor of up to ten. The suit senses when you want to move your legs, and then it moves them for you, supporting both its weight and yours as it walks around with you in it.

I meet with Takatoshi Kuno, the Sales Division Manager of Cyberdyne Inc., who has agreed to show me how HAL works. It’s just him; putting the exoskeleton on and getting it set up requires the help of one single guy who knows what he’s doing, no more.

Step one is to attach the sensors that HAL will use to tell when I want to move my legs. I drop my pants and they wire me up, carefully placing two electrodes on each of my thighs, two on my quads, and one on either side of my waist. The hip motors require an additional three electrodes per side, but from what I could understand, attaching those would have involved some fairly intimate groping, and Kuno-san didn’t seem so inclined (not that I blame him).

There are controls on the hips to adjust the power going to the motors, and after fiddling with them for a minute, Kuno-san asks me to try to extend my leg. As I tense my leg muscles, I can hear and then feel HAL’s motors kick in with a high tech electric whine, and my leg slowly rises off the floor and extends itself as I watch it. It’s pretty freaking cool. All I’m doing is thinking about moving my leg to the point where my muscles start to kick in, and then the suit picks up on that and does all the work.

Kuno-san pushes some buttons on the suit’s hip controls, gives me a little smile, and tells me to try it again. I start to tense my muscles and then WHAM! My leg rockets straight out in front of me in what feels like about a millisecond. This is when it really hits me: I’m actually wearing a powered exoskeleton, and it’s entirely possible that at this moment, I have the strongest legs on the entire planet.

From a standing position, walking just involves thinking ‘walk’ up to the point where your leg muscles start to do their thing, and then the suit figures out what you want and moves your legs accordingly. At first, I don’t really get this, and I try to move my legs by myself. It’s not intentional, but my brain simply isn’t accustomed to having something else do my walking for me. As it turns out, the best way to walk in HAL seems to be to just be super lazy and rely completely on the suit to take over for as many of your muscles as it possibly can.

This is not to say that HAL is just some mindless leg moving machine. In fact, it’s the opposite. HAL pays close attention to your muscle movements and can actually sense how much muscle you’re planning to apply, and it calculates how much power to add and moves its motors before your muscles move on their own. This means that that you still have complete control over when you take a step, where you take a step, and the length and height of your stride. When you get the hang of it, which took me barely five minutes, it’s really just like walking, except using robot muscles instead of your own.

After a few trips up and down the stairs and some more walking around, I’m feeling totally comfortable in HAL. The suit supports its own weight, so it effectively weighs nothing when you have it on, and when you stop trying to walk with your legs and let the suit move them for you, the entire experience becomes virtually seamless. And then just when I’m starting to relax, it’s time to sit down and take the suit off. I’m incredibly sad as HAL powers down and returns to its limp, dead robot look… I was only in it for ten minutes, but it already feels a little bit like a part of me.

If this sounds like something you’d like to try, and you have a valid medical reason to try it, the place to go is Jacksonville, Florida. A cybernetic treatment center will open there in the next few months.

As for that non-medical version of Cyberdyne’s exoskeleton that I tried out? They’re not available in the United States, sadly, but in Japan, Cyberdyne has almost a thousand of them helping people who have to lift heavy things for a living. My hope, and it’s been my hope ever since that 2011 demo, is that eventually these things will be available for rent at your local hardware store, so that next time you need to help a friend move a couch a cybernic suit can do some of the heavy lifting for you.

source: www.spectrum.ieee.org